The Roots of Educational Extension: From the UK to Canada

The idea of making knowledge accessible beyond the walls of traditional universities, now known as educational extension, has deep roots in the United Kingdom, where it emerged as a socially transformative force. The University of Cambridge’s Institute of Continuing Education, established in 1873, is widely recognized as the world’s oldest university department devoted to educational extension. It marked the beginning of what would become the global university extension movement.

The early extension efforts were driven by forward-looking thinkers and reformers like Anne Clough, a suffragist who championed the cause of higher education for women. In 1867, she worked with the North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women to commission a series of public lectures by James Stuart across five English cities. These lectures were not just academic. They were a form of social intervention, intended to expand educational access to girls and women previously excluded from formal learning spaces. This initiative planted the seeds of what would become known as the ‘university extension’ movement, which soon took hold at Cambridge and Oxford universities.

Oxford’s contribution came in 1878 with the formation of the Standing Committee of the Delegacy of Local Examinations. The first “Oxford Extension Lectures” were delivered in Birmingham by Reverend Arthur Johnson. By 1893, Oxford’s network of University Extension Centers was reaching learners across much of England and into Wales.

The university extension movement was about more than just travelling lectures. It was an attempt at democratizing knowledge and who could gain access to it. The movement reflected the belief that universities should serve society more broadly, by offering additional learning opportunities to those unable to enroll in traditional programs.

These ideals soon crossed the Atlantic Ocean. Inspired by these British models, Canadian universities began experimenting with their own extension programs in the late 19th century. While the structure and longevity of these efforts varied across institutions, the foundational idea remained the same: to “carry the university to the people,” bridging the gap between academia and community. The legacy of this movement lives on today in Canada’s many programs in continuing, extended, and adult education, serving learners of all ages and backgrounds.

Carrying the University to the People: The Crucial Role of Extension Services in Canada

Canada’s commitment to education goes far beyond the walls of traditional classrooms. Through extension services — both agricultural and educational — universities have for more than a century played a vital role in strengthening communities, addressing social change, and expanding access to learning.

Extension services are a lifeline that connect higher education institutions to the broader public. As William James Dunlop, a pioneer in continuing education at the University of Toronto, once said, “University Extension is the system of piping by which the water from the fountain [of knowledge] is carried out to those who cannot enter.”

Educational Extension: Lifelong Learning Across Generations

Educational extension in Canada dates back to the 19th century and remains deeply embedded in the mission of many universities. Queen’s University was the first to formally offer extension courses in 1878, primarily to help teachers upskill. By 1889, it was allowing students to study from home, effectively launching one of the earliest forms of distance education in North America.

McGill University began offering experimental off-campus lectures as early as 1859, which eventually grew into the Department of Extension, and later the School of Continuing Studies. Similarly, the University of Toronto formalized its efforts with the establishment of a Senate Committee on University Extension in 1894, inspired by efforts in England and the U.S. to democratize higher education.

The University of British Columbia (UBC), launched its Department of University Extension in 1936 during the Great Depression. According to Robert England, the department’s director in 1937, “Education is a form of emancipation from prejudice, narrow views and hasty generalization. The University can do little more than provide avenues of opportunity along which people can march more confidently to a better future.”

Today, educational extension continues to thrive. Institutions like Saint Mary’s University, the University of Waterloo, the University of Manitoba, and the University of New Brunswick all offer vibrant continuing education and lifelong learning programs in Canada that support professional development, personal enrichment, and community empowerment.

Agricultural Extension: Innovation Rooted in the Land and Research

While educational extension has transformed learning opportunities for adults, agricultural extension has been equally transformative, especially in rural and farming communities. The concept involves transferring scientific research and innovative practices directly to farmers.

Canada’s first formal agricultural extension initiative began in Ontario in 1907, when the province placed six Ontario Agricultural College graduates in high schools to serve as agricultural representatives. These “ag reps,” as they came to be known, became essential links between the university, the government, and local farming communities. This model soon spread across the country, underpinning a broader movement toward practical, community-based problem solving in agriculture.

At the University of Saskatchewan, which was founded as an agricultural college, the first university-based department of extension in Canada was launched in 1910. It embodied the ‘Wisconsin Idea,’ which emphasized service to the broader public and applied research.

Dalhousie University, through its Faculty of Agriculture, and St. Francis Xavier University, through its Extension Department and the globally recognized Antigonish Movement, furthered these principles to focus on rural development and people-centered community renewal.

Legacy and Relevance of Extension Today

Scott McLean, a scholar from the University of Calgary, recently underscored the historical and contemporary importance of extension work: “Few realize that over the first half of the 20th century, far more Canadians participated in university-based adult education programs than enrolled as post-secondary students.”

From McGill University’s evening classes in the 1850s to Laval University’s adult education programs through Quebec’s Quiet Revolution, extension services in Canada have continuously adapted to social shifts, responding to urbanization, economic crises, wars and foreign conflicts, and educational demands. McLean noted, “The story of adult education at Laval is rooted in the broader history of university extension and in the social history of Quebec.”

Extension services have served not just as educational programming, but as engines for community engagement, social progress, and economic resilience. As institutions like the University of Alberta, University of Calgary, Memorial University, and others continue this legacy, they echo a mandate that has always been clear: “carrying the University to the people.”

In a rapidly changing world where knowledge, skills, and innovation are more vital than ever, extension services remain a cornerstone of Canada’s educational and agricultural landscape with a proud tradition of outreach, social and economic relevance, and personal empowerment.

Small World Networks and Web 3

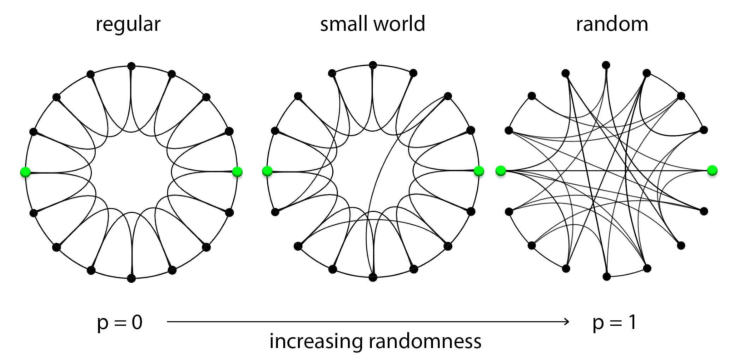

Underlying the success of extension movements past and present is the power of small world networks (SWNs), where tightly-knit local clusters are linked by key connectors to broader distributed, centralized or decentralized systems. Educational and agricultural extension programs have historically thrived on this structure, where trusted local agents (such as lecturers, ag reps, or community leaders) act as bridges between formal institutions and grassroots communities.

In the context of Web 3, SWNs may become even more critical. Decentralized networks rely on peer-to-peer trust, local relevance, and shared knowledge to scale participation and innovation. Here, our extended self, comprising our digital identities, social affiliations, and informational receiving and sharing, serves as a node within these networks, allowing individuals to fluidly move between localized interactions and global systems. This dynamic mirrors the architecture of decentralized ledger technologies, where knowledge, power, and value are distributed and decentralized, yet connected through meaningful, purpose-driven ties.

Extension services naturally form small world networks that bridge formal knowledge systems with local communities and practical activities of everyday life. Our extended selves act as connectors in these networks, shaping how we engage with and build decentralized Web 3 digital ecosystems.

Web3 Extension Services: Expanding Access in the Digital Frontier

Just as educational and agricultural extension services brought universities into classrooms, farms, and communities, a new kind of outreach is emerging to meet the challenges and opportunities of the electronic-digital age. Web 3 Extension Services (W3ES) represent the next frontier. This new type of extension service is starting to offer accessible, community-centered pathways for understanding and engaging with decentralized Web 3 technologies, and together with them, the growing digital economy.

Much like early university extension models made sense of formal education for those excluded from it, W3ES can help the public navigate and frame the complexity of Web 3 business, personal identity and governance. W3ES can help raise awareness about concepts such as consensus mechanism, decentralized finance (DeFi), NFTs, decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs), and self-sovereign digital identity, through workshops, tools, and participatory platforms designed for broad, equitable access.

By connecting people to digital literacy and teaching clarity regarding personal agency within emerging technological ecosystems, W3ES echo the tradition of using education as empowerment. They provide not only technical skills but also frameworks to critically engage with the social, economic, and political implications of Web 3, such as data ownership, platform governance, private identity, wallets and self-sovereign digital ID, and the future of work and education.

Much like agricultural extension helped rural communities adopt innovations that improved livelihoods, W3ES can support communities in leveraging decentralized tools for local economic development, civic engagement, and various competitive-cooperative models of value creation. As universities and public institutions explore their roles in this space, the legacy of educational extension provides a powerful blueprint. It’s up to us as architects, builders and users to ensure it is one rooted in trust, personal safety, individual and community relevance, and overall accessibility of online activity to knowledge and multiple competing or cooperating hypotheses, histories or interpretations. W3ES helps organize the chaos of language(s) options enabling coordination, orchestration, cooperation and training towards common goals as defined by those directly involved in each and every ecosystem’s emergence, growth and extension.